On the outskirts of one of Cornwall’s major towns sits a sleepy suburb, Nansledan. Recently built and immaculately kept, Nansledan is the property of the Duchy, in other words the property of William, Prince of Wales.

The project was originally begun by his father, now-King Charles as a punt at easing Cornwall’s housing crisis in a sustainable fashion. Yet there has been suspicion raised that it is indeed exacerbating the problems of that crisis and making the local ecology and economy worse off.

A Tour.

The entrance to newbuild reads “The Duchy of Cornwall. Nansledan: A Thriving Community.” – the sign clearly imploring those who enter the gates of this utopian project to take notice of the Duchy’s fine work. Everywhere, plastered inside and outside of the estates, exists what can shortly be described as propaganda. Tales of the ecological conservation work, sustainable energy production, and minute attention to detail in community building are omnipresent.

The town, at least for now is largely vacant. Though some young parents play with their children or chat in the cafes, and slightly fewer elderly residents run errands or see friends at bingo nights, between the hours of 7am and 6pm, this town is barren.

Communal areas, which according to proponents of the project are Nansledan’s primary appeal, are regulated with a series of laws, including a prohibition on scooters, bicycles, and ball games. These laws are not heavily enforced, but the tendency of residents to remark on them, amongst the various other 83 laws that come neatly packaged in resident handbooks, shows their effect on the mentality there.

“Big Brother respectfully asks you adhere to following these rules…”

Though trite to say about newbuild estates everywhere in the UK, the town feels eerie. Though not a critique in itself, it doesn’t “feel” particularly Cornish. And with the hum of American architectural inspiration in the air, Nansledan feels like the kind of place built for nuclear demolition in a 1950s Arkansas desert.

“Surfbury” the Crown’s no.2 toy town.

The suburb, the construction of which began in 2013, was nicknamed “Surfbury”, a play on Poundbury. A Dorset suburb, famed as an experiment in urban development for the Duchy of Cornwall, Poundbury has received a reputation for creating an idyllic and quaint life for its residents.

Poundbury began its construction in 1993 under the watchful eye of Léon Krier, an eccentric academic and architect who held a reputation for despising modernism and striving for expansion of suburbia. And despite not leading the project, Charles was also incredibly hands-on with the process, with a keen interest in architecture and urban planning.

This model was then replicated in Nansledan, and the information distributed about the towns are largely similar. Every time the two are written or spoken about in public, the attempts to justify the existence of each by citing statistics of economic productivity are emphatically emphasised.

“A Sustainable Cornish Community.”

The press around Nansledan, when not labouring on the point of its economic fertility, labours on another PR staple for the modernised institutions of Crown and state – environmental sustainability. According to its advocates, Nansledan is a town built for the future, a hub of community which functions on self-reliance and environmental viability. But peeling back the layers of Nansledan’s good press reveals a pretty solid case for accusing the Duchy of causing more environmental and economic damage than would ever be admitted to by the Duchy or pro-Royal press.

As a starting point, Nansledan is far away from everywhere and well-connected to nowhere. Despite sitting on the outskirts of Newquay, one must travel a while before reaching anywhere residents could work or access the rest of civil society.

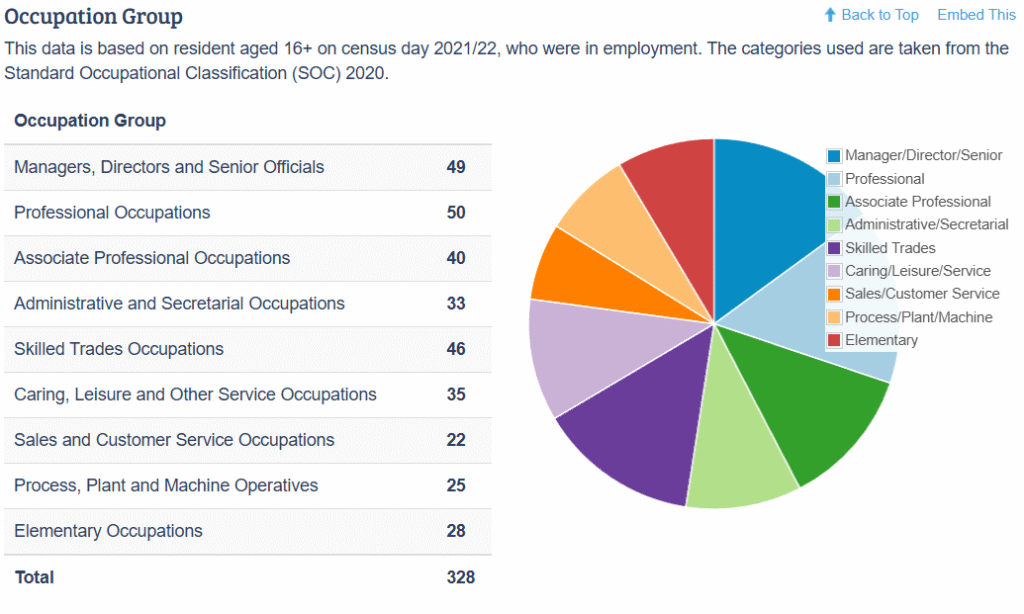

To be frank, Nansledan is a “commuter town”, heavily reliant on resident’s ability to drive in order to work and live. This is only exacerbated by the professional demographics of the town – which according to the most recent set of census data – is dominated by members of the professional managerial class, as well as lower-middle class trades workers. These sectors require that residents either work from home, or more likely, drive in and out of the town to work. Public transport in and out is slightly better than in most of Cornwall, but with it situated at a distance from anywhere else, Nansledan still exists as an island all on its own. Not only does this hamper the ability of the community to grow and thrive in the organic way that is often advertised but also breaks down any illusion of sustainable urban development.

The PMC and petite-bourgeoise demographics of Hynsledan Lugan, Nansledan.

And whilst the checks and balances of ecological sustainability have been covered by the Duchy in their construction of Nansledan, sustainability is about much more than minimal tinkering. As aforementioned, socioeconomic and ecological phenomena go hand in hand, and have significant effect on each other. Projects oriented around ecological sustainability cannot be focussed solely about plants and birds, and require systemic analyses and change, something unlikely to come from the Duchy of Cornwall.

Ragwort, a “coloniser plant” often found on or near newbuild housing estates amongst building waste.

This is amongst other quirks of the town’s development and regulation – including the prohibition on private residents fixing solar panels to their rooves. The literature on Nansledan as a sustainable model for new builds in the UK is pretty monotone, but easy to look through with an understanding of sustainability that extends beyond what is often labelled as “greenwashed” PR.

Misunderstanding the Housing Crisis.

Similar examples of doting PR has come from the verbal commitment of the Duchy to house the houseless in Cornwall. According to the Prince of Wales himself, the Duchy has set aside 24 houses for temporary accommodation for the homeless in Cornwall. This is out of the projected 4,000 homes set to be built by the projects completion in 2030.

Alongside this rather pitiful excuse of a PR job, an additional 30% of the houses have been set aside as so-called “affordable houses”. This statement on its own raises a very simple question: affordable for whom? Affordability is a designation that requires a house to be 20% below market rate, but for the majority of young people, who 40 years ago would’ve been able to secure a place on the housing ladder and achieve the status of “home-owner”, this is still far too high. And as for the homeless in Cornwall, who by most estimates make up c.1,500 people, this is a pathetic response to the spiralling crisis.

According to many experts, the problem of housing in the UK is not supply, it’s distribution. The nature of Britain’s property law prevents some from secure living entirely, often paying exorbitant rents or high mortgages, and allows others – such as the Prince of Wales – to hold portfolios reaching out into the hundreds or thousands. For Cornwall in particular, the 14,000 second homes in the peninsula causes economic hardship, by driving up prices of all houses on a regional level, as well as social and political resentment towards those with a higher degree of purchasing power than the average Cornish resident.

Ultimately, the token commitment to tackling the housing crisis needs to be viewed in context. For Nansledan’s ongoing construction, the Duchy has partnered with 3 housing developers: Wain Homes, Morrish Homes, and CG Fry and Son. The latter of the trio, also woven into the development of Poundbury, holds over £100 million in assets and regularly makes profits exceeding £10 million. Those looking to Nansledan for environmental or community-oriented development must remember that it is a profit-driven project like any other – only this time orchestrated by the Duchy and the Crown.

Rejecting NIMBYism and questioning the Crown.

Nansledan has, of course, received criticism. Many in Cornwall feel it is an imposition, and have taken up what newbuild advocates call a NIMBY attitude to the development of the new build estates. But in this instance it is different.

It is different because the Duchy of Cornwall owns a total of 135,000 acres of land from Cornwall to Kent. And Nansledan acts as an example of just how much power the Prince of Wales still has in modern Britain. These North Cornwall estates manifested from thin air in 2013, for the purpose of housing the English middle-classes.

And if the Monarchy, an apparently-symbolic institution in the 21st century, can erect these structures, which effect our ecology, economy, and society, with very little democratic consultation, it prompts certain questions.

The most obvious question is what does that do to our relationship with the King and his sons? Are we citizens of a very limited and liberal parliamentary democracy, or are we subjects of Dukedoms? Do we have a say on the decisions made on neighbouring land, or is this region of the UK to be subjected to the whims of eccentric princes and esoteric architectural visionaries?

Images Via: Cobblestone Media.

Leave a Reply to Rob Rooney Cancel reply