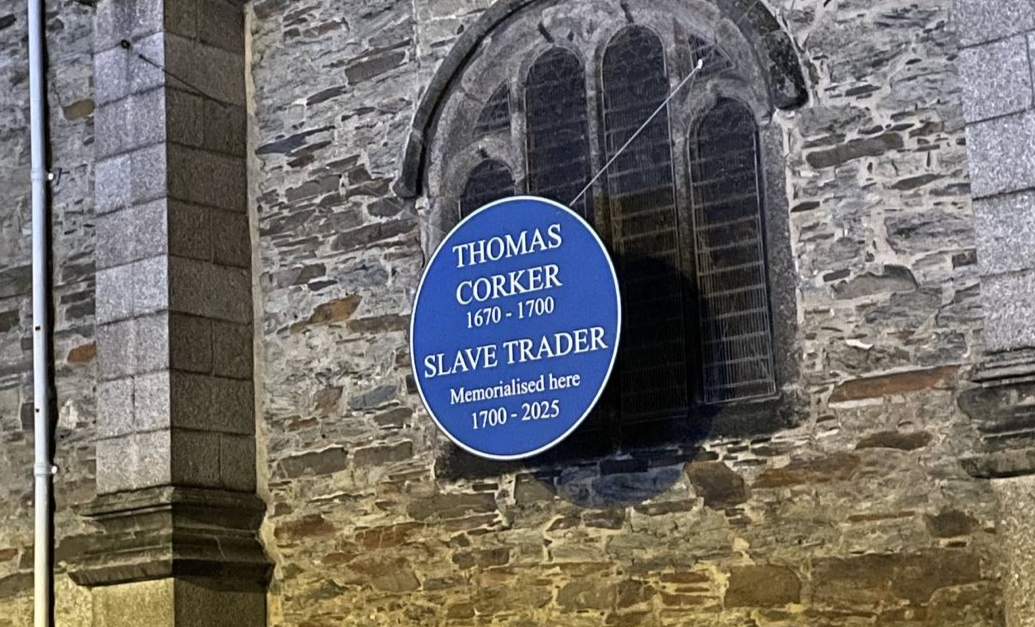

History has always been about who we mourn, who we memorialise, and who we bury without a name. Western institutions that were endowed by empire still continue to display memorials of powerful white men – now resoundingly shown to be the villains of history – whilst leaving their victims unnamed and unacknowledged. One such memorial is to a Slave Trader, Thomas Corker, displayed in the King Charles the Martyr Church in Falmouth.

“A very negligent and extravagant life.”

Thomas Corker was England’s chief agent in the Royal African Company, playing a central role in the trafficking of enslaved African people across the Atlantic to the Americas. The Company shipped more enslaved men, women and children to the Americas than any other trading company in the world.

Corker’s trading legacy was marked with fraudulent practice of embezzlement and unauthorised trade, and he was subject to sharp criticism within his lifetime, due to the poor conditions slaves would arrive in under his management. Inhabitants aboard the slave ship the ‘Edward and William’ arrived to Jamaica in such poor conditions that even RAC officials were reportedly “appalled”. This incident contributed to the company’s growing mistrust of him and eventually Corker was dismissed, due to his alleged record of “living a very negligent and extravagant life.”

He was memorialised around the date of 1700, in marble and limestone, by his brother Robert Corker, who was serving as Falmouth Mayor at the time. The Latin inscription is particularly extravagant, and rare for memorials that usually favour basic fundamental details. In Corker’s inscription it states that “he was a glory to the English and the Africans”, celebrating his participation in the transatlantic trade in enslaved African people.

Public memory and Power.

Public memory is not a neutral or objective reflection of the past, but rather it is curated by prevailing power dynamics. Institutions such as the Church, the state, and elite families have exerted influence over exactly who and what remembered through the erecting and maintaining of memorials. These acts of remembrance can never be neutral as they are constructed by social, political and cultural forces. Certain narratives are preserved whilst others are omitted.

Following the Restoration, memorials like Corker’s were increasingly created to commemorate the dead as moral examplars, “encouraging the living to not only remember the deceased, but also to reflect upon their achievements and aspire to similar virtues.” Memorial inscriptions can historically hold lone authority on how people understand the legacy of the deceased. These records are not just a documentation of the past, but a shaping of the present, as they encode values and perpetuate legacies through narrative construction that dispels violence, and are an indication of the racial system that continues to enable Corker’s legacy.

Corker’s memorial continues to be preserved, whilst completely divorced from the brutality of Black suffering it is rooted in. It functions as an instrument of erasure, preserving a fictionalised version of the past that continues to paint him as “a glory to English and Africans”. It is an explicit exercise in narrative construction, presenting Corker in a way that valorises him with favourable preferences for his remembrance.

The Church fears the truth around slavery, as it tallies their debt. To speak on such matters is to set a precedent of how they must further deal with monuments with a colonial history, of which the Church has many.

The Rogue’s Gallery in King Charles the Martyr Church.

In the King Charles the Martyr Church alone, there are a number of memorials with colonial links. Aside from Corker, the most notable is William Henry Sleeman who’s legal frameworks contributed to imperial control over India. Similarly, Joseph Banfield, a shipping agent for Camden, Calvert & King, traded in slaves. The Church also has a memorial to John Navarre Macomb, a New York merchant who’s family household had at least 12 enslaved Africans.

If the church had honest and true intent to correct history under Historic England’s advised ‘retain and explain’ method, there would be information alongside each of these memorials respectably. But instead the strategy has been delay and deflection. Despite knowing of the atrocities these people committed, the only one to be under any review is the Corker memorial, due to mounting public pressure and protest. Preservation is not shown as education of history, but about protecting the reputations of the church through a kind of curated silence. Historical reference is ignored in order to avoid reckoning of accountability.

Preservation, when divorced from truth, becomes nothing more than propaganda. The Thomas Corker memorial is not maintained as a commitment to honest historical reflection, but rather prevails through continued restoration to conserve a romanticised fiction. Each act of maintenance, whether that be polishing, painting, or restoring the stone, is an act of cultural amnesia, smoothing over the brutal reality of a man who built his fortune on the suffering and dehumanisation of thousands.

The grandeur of the monument, from the elegant inscription to the carefully carved stone, does not educate: it anesthetises. It transforms an enslaver into a figure of esteem, allowing the cycle of white supremacy to continue beneath a façade of historical interest. The enslaver becomes the educator. The aggressor becomes the remembered. And the enslaved are forgotten. Their absence is not accidental, it is a feature of how these monuments must function. We are told that to remove the memorial would be to erase history, but this monument was never about remembering truth: it was about preserving power. And so to destroy it would not be historical vandalism, but an act of historical correction.

Corker must fall.

When recounting the argument that removing or destroying the memorial is ‘erasure of history’, there is of course, the true tragedy of erasure to which those making the argument fall silent: the lost history of the enslaved. If we are to mourn truth and accurately record, the place to start would be from the countless unmarked graves, cultures disrupted, and oral histories lost that came as a direct result of figures like Corker. His memorial stands as an emblem of erasure, glorifying the loss of the many histories he personally struck from record.

Let this shrine of supremacy crumble to dust, in the knowledge that its destruction wouldn’t be that of history, but of the propping up of a lie. In its place we must create space for another version of history, no longer written by the colonisers. The enslaved deserve more than absence through forced silence, they deserve space, dignity and memory.

Image Via: Cobblestone Media.

Leave a Reply